Zur Leitseite www.schumpeter.info

Berichte des Manchester Guardian und der Times über

Joseph Alois Schumpeters Vortrag

The Instability of Our Economic System

Bemerkung des Herausgebers

Am 2. September 1927 hielt Schumpeter auf der Tagung der Britisch Association for the Advancement of Science in Leeds einen Vortrag zum Thema "The Instability of Our Economic System". Dieser Vortrag wurde von der Tagespresse zum einen mit Blick auf die Frage nach der Systemstabilitaet zum anderen mit Blick auf die damals aktuelle Frage des Goldstandards referiert. In einem Brief an Gustav Stolper schrieb Schumpeter am 17. Oktober hierzu: ..."mein Vortrag wurde sehr freundlich aufgenommen, von allen großen Zeitungen in schlechten Auszügen gebracht."

Zunaechst der Bericht des Manchester Guardian vom 3. September 1927 unter der redaktionellen Ueberschrift "Is the capitalist system stable?"

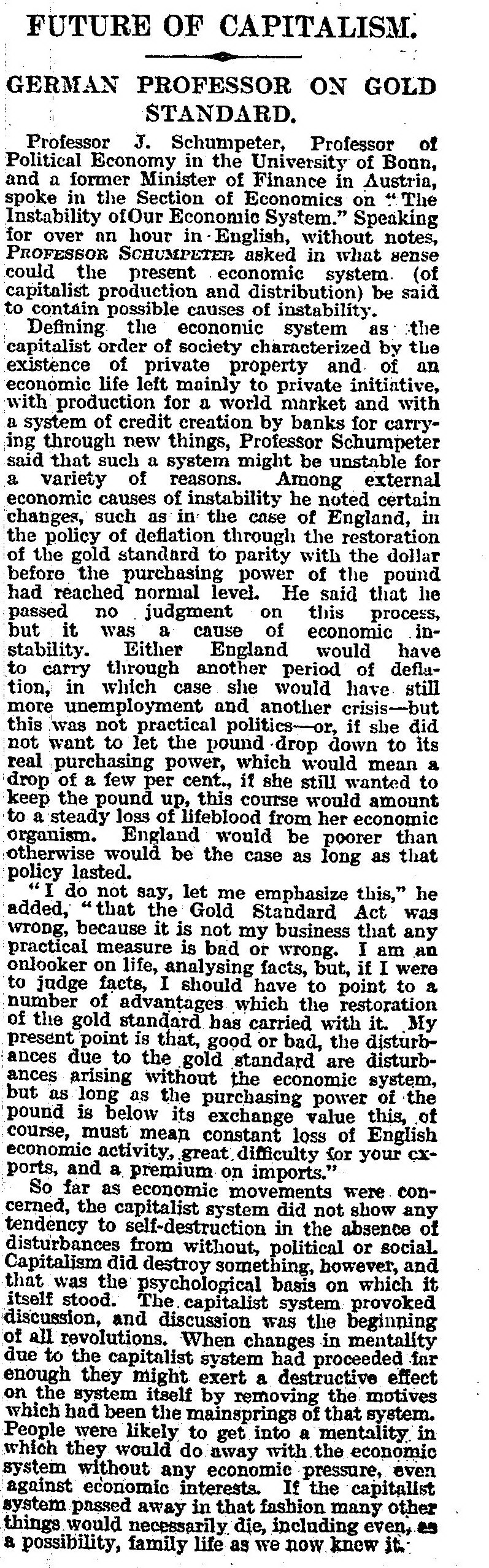

The Times berichtete ebenfalls am 3. September: "Future of Capitalism - German professor on gold standard". Im Unterschied zum Guardian hebt sie mit ihrer Wiedergabe u. a. das Schumpetersche Systemcharakteristikum einer Produktion für den Weltmarkt hervor. Ich veroeffentliche diesen Bericht hier nach seiner Darbietung durch das Digitalarchiv der Times.

Is the capitalist system stable? German Professor´s answer

Is the capitalist system a stable one? Professor J. Schumpeter, of Germany, told the Economic section that he believed it was if left to itself, but that in its working it had evolved a mentality in people and a way of arranging and looking at life which undermined the psychological basis necessary to its continuance. Professor T. E. Gregory, of the London School of Economics, supported Professor Schumpeter to some extent, and expressed the view that the only thing that could upset the capitalistic system was war.

In the course of the day's discussions on education the Duchess of Athol pleaded for more practical work in the English curricula and for the development of the central school. Dr. Alfred Mumford, of Manchester, reinforced from his own special investigations the view that physical fitness and scholastic achievement almost invariably went together.

The Engineering section spent the larger part of the day considering the difficulties of evolving an ideal way of utilising our coal supplies.

Is capitalism stable?

The address of Professor J. Schumpeter, Professor of Political Economy at Bonn, and formerly Minister of Finance in Austria, on "The instability of our economic system," attracted a large audience.

By the capitalistic system, he said, we mean the economic order characterised by:

(1) Private property and private initiative, (2) production for the market and the division of labour; (3) the important device of credit creation by banks, which, however, he stood alone in considering an essential element of that system.

This thesis simply was that the capitalistic system was economically stable in itself and would therefore last indefinitely if left to itself, but that by its own working it evolves a mentality in people and a way of arranging life and looking at life, which was bound to undermine what were the indispensable psychological bases of capitalistic society. He further submitted that this psychological process was already to be seen to be in full swing, as shown by our modern attitude towards taxation, inheritance, home life, and so on, quite irrespective of, and, indeed, running counter to, economic necessities.

Capitalism meant (to use a term of Professor Macgregor's) a rationalisation of minds. In the Middle Ages people lived in an environment essentially stable. There were the church, the castle, the village community, the communal processes, which carried things on year after year in essentially the same way, and neither church nor castle were discussed. There was no reason to discuss them. Discussion was always the precursor of revolution. Thus the environment of the day made the minds of people stable. It was not a system of castle and churches to which they were attached, but a certain visible church and castle and community and a family life quite different from the modern family life. It was an essentially traditional way of life and thinking.

These did not exist any more. Capitalism, with its private property and the motives of private property, was tending to destroy them. It broke up the village community and two things necessarily followed.

People lost their sense of anything absolute existing and of the existence of something which commanded allegiance irrespective of personal judgment. Hence they were thrown on their own resources. They had to fight their way on slippery ground, and doing so naturally focussed their attention on the rationality of their behaviour, on producing something that would fetch what it had cost at least.

The feeling of dependence on their own judgment influenced their culture, duty, mentality, religion, art, and so on. It tended also to cut a man off from all his humanities to other persons and things which in the past were among the most valuable of stimulants. Many of the things dear to our fathers were dear to us no more. Not only the bonds which formerly bound an employer to his factory and workpeople, but also the bonds of private life, the relations of man and wife, of parents and children, did not mean now what they meant when they were a necessary form of survival.

The first step in the argument leading up to his thesis, Professor Schumpeter continued, consisted in proving the existence under competitive conditions of a stable equilibrium of the economic process to which, in given circumstances, real life tended to conform itself. This proof was well established by modern analysis and its great master, the late Dr. Alfred Marshall. It was true that the theorem referred to did not as a rule command the consent of the man in the street, who in our days was in the habit of attributing to competition all sorts of instability, but he mostly did so under some misapprehension.

The competitive conditions which prevailed during the nineteenth century certainly did not prevail any more, and it was necessary therefore to prove a similar proposition in the case of monopolised industry. This was less easy to do, and many of the highest authorities did not admit the existence of a stable equilibrium of economic life in this case, which nevertheless could be shown to exist. Similarly it could be proved that increase of population is never by itself a cause of economic instability.

Booms and Depression.

There remains the fact of the business cycle, destroying as it did any state of equilibrium which might have established itself. The business cycle could not be accounted for by outside impulses, such as harvests, wars, and so on, but was, on the contrary, the necessary form economic evolution took under capitalistic conditions. But although every boom destroyed an equilibrium every depression tended to establish a new one, and there was nothing in these recurring waves of prosperity and depression to affect the capitalistic system as such, nor were extensions and contractions of banking credit causes of instability, as held by high authority.

But economic stability in the sense defined by the preceding argument did not either imply or guarantee political or social stability, and an economic situation perfectly stable in itself might still be socially or politically unstable for a variety of reasons. Political and social circumstances of our days were in fact unstable in the highest degree.

It might seem that if instability were there the proof by a theorist that this instability was not due to the economic system might seem of little value, but the speaker pointed out that in the case of an illness it was not entirely a matter of indifference to know, even for practical purposes, what the illness consists in and in what parts of the organism it originated.

With the present particular order of social things, Professor Schumpeter concluded, many other things would necessarily die, and there were others that might or might not - family life, for instance,- but there was no need to be afraid of that, because in social life it was very much as in physical life, as long as we really valued a thing we proved that it was not dead. It only died if we wanted to let it drop. Death, indeed, stepped up to us very often in the bloom of youth and efficiency, but it was not the normal habit of death to come to us thus. It usually and normally came after a long life, after we were worn out by disappointment and illness; after we had had enough to want to live any more, and the same applied to social things.

Professor Gregory's Comments.

Professor T. E. Gregory, of the London School of Economics, opening the discussion that followed, said that the important things to most of them in the address was the conclusion that there was nothing that, looked at from the strictly economic standpoint, threatened the existing order of society except the reactions of existing institutions and processes on the minds of men.

Most of the vast amount of discontentment with the existing economic order rested on a complete misunderstanding of what the existing economic order really was, but capitalism was being constantly threatened by social and political difficulties, and the question was what was the maximum degree of interference the existing order was capable of sustaining without toppling down by virtue of the undermining of its foundations; to what extent would labour discontent have to go before it seriously threatened it.

Experience of recent years seemed to indicate that labour discontent could take on very violent forms without threatening capitalism very seriously, because some of the attacks constantly made on existing institutions recoiled on the heads of their authors. The general strike as a method of toppling over capitalism did not prove a success.

Were there any other economic causes likely to undermine effectively the working of existing institutions? He could see only one. The real cause which would break down capitalism, if anything did it, was war. The real danger before the modern world was the danger of such a state of international tension that the working of economic institutions would be so entirely subordinated to warlike purposes that capitalism, in the sense of the free working of private enterprise, would be made impossible.

Quelle: The Manchester Guardian, September 3, 1927, page 16

* * * * *

DER BERICHT DER TIMES :

Quelle: "Future Of Capitalism." The Times [London] 3 Sept. 1927: 6. The Times Digital Archive.16 Apr. 2014.

Zur Leitseite www.schumpeter.info